JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

ª 2017 BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION

ISSN

0735-1097/≥36.00

PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER

APPROPRIATE USE CRITERIA

ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/

STS 2017 Appropriate Use Criteria for

Coronary Revascularization in Patients

With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

A Report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force,

American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association,

American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology,

Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography,

and Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Coronary

Manesh R. Patel, MD, FACC, FAHA, FSCAI, Chair

David J. Maron, MD, FACC, FAHA

Revascularization

Peter K. Smith, MD, FACC†

Writing Group

John H. Calhoon, MD

Gregory J. Dehmer, MD, MACC, MSCAI, FAHA*

*Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions

James Aaron Grantham, MD, FACC

Representative. ySociety of Thoracic Surgeons Representative.

Thomas M. Maddox, MD, MSC, FACC, FAHA

Rating Panel

Michael J. Wolk, MD, MACC, Moderator

Peter L. Duffy, MD, FACC, FSCAI*

Manesh R. Patel, MD, FACC, FAHA, FSCAI,

T. Bruce Ferguson, JR, MD, FACC‡

Writing Group Liaison

Frederick L. Grover, MD, FACC‡

Gregory J. Dehmer, MD, MACC, FSCAI, FAHA,

Robert A. Guyton, MD, FACC‖

Writing Group Liaison*

Mark A. Hlatky, MD, FACC‡

Peter K. Smith, MD, FACC, Writing Group Liaison

Harold L. Lazar, MD, FACC¶

Vera H. Rigolin, MD, FACC‡

James C. Blankenship, MD, MACC, MSCAI‡

Geoffrey A. Rose, MD, FACC, FASE#

Alfred A. Bove, MD, PHD, MACC‡

Richard J. Shemin, MD, FACC‖

Steven M. Bradley, MD§

Jacqueline E. Tamis-Holland, MD, FACC‡

Larry S. Dean, MD, FACC, FSCAI*

Carl L. Tommaso, MD, FACC, FSCAI*

This document was approved by the American College of Cardiology Clinical Policy Approval Committee on behalf of the Board of Trustees in

January 2017.

The American College of Cardiology requests that this document be cited as follows: Patel MR, Calhoon JH, Dehmer GJ, Grantham JA, Maddox TM,

Maron DJ, Smith PK. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/STS 2017 appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization in patients with stable

ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery,

American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography

and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:XXX-XX.

This document has been reprinted in the Journal of Nuclear Cardiology and the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

Copies: This document is available on the World Wide Web site of the American College of Cardiology (www.acc.org ). For copies of this document,

Permissions: Multiple copies, modification, alteration, enhancement, and/or distribution of this document are not permitted without the express

permission of the American College of Cardiology. Requests may be completed online via the Elsevier site (http://www.elsevier.com/about/policies/

2

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

L. Samuel Wann, MD, MACC**

‖Society of Thoracic Surgeons Representative. ¶American

Association for Thoracic Surgery Representative. #American Society

John B. Wong, MD‡

of Echocardiography Representative. **American Society of Nuclear

Cardiology Representative.

‡American College of Cardiology Representative.

§American Heart Association Representative.

Appropriate Use

John U. Doherty, MD, FACC, Co-Chair

Warren J. Manning, MD, FACC

Criteria Task

Gregory J. Dehmer, MD, MACC, Co-Chair

Manesh R. Patel, MD, FACC, FAHA§§

Force

Ritu Sachdeva, MBBS, FACC

Steven R. Bailey, MD, FACC, FSCAI, FAHA

L. Samuel Wann, MD, MACC††

Nicole M. Bhave, MD, FACC

David E. Winchester, MD, FACC

Alan S. Brown, MD, FACC††

Michael J. Wolk, MD, MACC††

Stacie L. Daugherty, MD, FACC

Joseph M. Allen, MA

Milind Y. Desai, MBBS, FACC

Claire S. Duvernoy, MD, FACC

††Former Task Force member; current member during the writing

Linda D. Gillam, MD, FACC

effort. ††Former Task Force Co-Chair; current Co-Chair during the

Robert C. Hendel, MD, FACC, FAHA††

writing effort. §§Former Task Force Chair; current Chair during the

Christopher M. Kramer, MD, FACC, FAHA‡‡

writing effort.

Bruce D. Lindsay, MD, FACC††

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

■

Section 1. SIHD Without Prior CABG

■

Table 1.1 One-Vessel Disease

■

PREFACE

■

Table 1.2 Two-Vessel Disease

■

■

1.INTRODUCTION

■

Table 1.4 Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

■

2.METHODS

■

Indication Development

■

Table 2.1 IMA to LAD Patent and Without Significant

Stenoses

■

Figure 1 AUC Development Process

■

Table 2.2 IMA to LAD Not Patent

■

Scope of Indications

■

Which Coronary Revascularization May Be

3.ASSUMPTIONS

■

Considered

■

General Assumptions

■

Table 3.1 Stable Ischemic Heart Disease Undergoing

Procedures for Which Coronary Revascularization

Assumptions for Rating Multiple Treatment Options . . ■

May Be Considered

■

4.DEFINITIONS

■

7.DISCUSSION

■

Table A. Revascularization to Improve Survival

Compared With Medical Therapy

■

APPENDIX A

Table B. Noninvasive Risk Stratification

■

ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/STS

2017 Appropriate Use Criteria for Coronary

5.ABBREVIATIONS

■

Revascularization in Patients With Stable Ischemic

Heart Disease: Participants

■

6.CORONARY REVASCULARIZATION IN PATIENTS

APPENDIX B

WITH STABLE ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE:

APPROPRIATE USE CRITERIA (BY INDICATION)

■

Relationships With Industry and Other Entities

■

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

3

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

ABSTRACT

Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American

Association for Thoracic Surgery, and other societies,

The American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardio-

developed and published the first version of the AUC for

vascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of

coronary revascularization in

2009, releasing the last

Thoracic Surgeons, and American Association for Thoracic

update in 2012. The AUC are an effort to assist clinicians

Surgery, along with key specialty and subspecialty soci-

in the rational use of coronary revascularization in

eties, have completed a 2-part revision of the appropriate

common clinical scenarios found in everyday practice.

use criteria (AUC) for coronary revascularization. In prior

The new AUC for coronary revascularization were

coronary revascularization AUC documents, indications for

developed as separate documents for stable ischemic

revascularization in acute coronary syndromes and stable

heart disease (SIHD) and acute coronary syndromes. This

ischemic heart disease (SIHD) were combined into 1 docu-

was done to address the expanding clinical indications

ment. To address the expanding clinical indications for

for coronary revascularization, include new literature

coronary revascularization, and to align the subject matter

published since the last update, and align the subject

with the most current American College of Cardiology/

matter with the ACC/American Heart Association guide-

American Heart Association guidelines, the new AUC for

lines. An additional goal was to address several of the

coronary artery revascularization were separated into 2

shortcomings of the initial document that became

documents addressing SIHD and acute coronary syndromes

evident as experience with the use of the AUC accumu-

individually. This document presents the AUC for SIHD.

lated in clinical practice.

Clinical scenarios were developed to mimic patient pre-

The publication of AUC reflects 1 of several ongoing

sentations encountered in everyday practice. These sce-

efforts by the ACC and its partners to assist clinicians who

narios included information on symptom status; risk level

are caring for patients with cardiovascular diseases and to

as assessed by noninvasive testing; coronary disease

support high-quality cardiovascular care. The ACC/

burden; and, in some scenarios, fractional flow reserve

American Heart Association clinical practice guidelines

testing, presence or absence of diabetes, and SYNTAX score.

provide a foundation for summarizing evidence-based

This update provides a reassessment of clinical scenarios

cardiovascular care and, when evidence is lacking, pro-

that the writing group felt were affected by significant

vide expert consensus opinion that is approved in review

changes in the medical literature or gaps from prior criteria.

by the ACC and American Heart Association. However, in

The methodology used in this update is similar to the initial

many areas, variability remains in the use of cardiovas-

document but employs the recent modifications in the

cular procedures, raising questions of over- or underuse.

methods for developing AUC, most notably, alterations in

The AUC provide a practical standard upon which to

the nomenclature for appropriate use categorization.

assess and better understand variability.

A separate, independent rating panel scored the clin-

We are grateful to the writing committee for the

ical scenarios on a scale of 1 to 9. Scores of 7 to 9 indicate

development of the overall structure of the document and

that revascularization is considered appropriate for the

clinical scenarios and to the rating panel—a professional

clinical scenario presented. Scores of 1 to 3 indicate that

group with a wide range of skills and insights—for their

revascularization is considered rarely appropriate for the

thoughtful deliberation on the merits of coronary revas-

clinical scenario, whereas scores in the mid-range of 4 to 6

cularization for various clinical scenarios. We would also

indicate that coronary revascularization may be appro-

like to thank the parent AUC Task Force and the ACC

priate for the clinical scenario.

staff—Joseph Allen, Leah White, and specifically, Maria

As seen with the prior coronary revascularization AUC,

Velasquez—for their skilled support in the generation of

revascularization in clinical scenarios with high symptom

this document.

burden, high-risk features, and high coronary disease

Manesh R. Patel, MD, FACC, FAHA, FSCAI

burden, as well as in patients receiving antianginal ther-

Chair, Coronary Revascularization Writing Group

apy, are deemed appropriate. Additionally, scenarios

Immediate Past Chair, Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force

assessing the appropriateness of revascularization before

Michael J. Wolk, MD, MACC, Moderator,

kidney transplantation or transcatheter valve therapy are

Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force

now rated. The primary objective of the AUC is to provide

a framework for the assessment of practice patterns that

1. INTRODUCTION

will hopefully improve physician decision making.

In a continuing effort to provide information to patients,

PREFACE

physicians, and policy makers, the Appropriate Use Task

Force approved this revision of the

2012

Coronary

The American College of Cardiology (ACC), in collabora-

Revascularization AUC (1). Since publication of the 2012

tion with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and

AUC focused update, the original nomenclature used to

4

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

characterize appropriate use has changed (2). New clinical

encountered in practice, it would be impossible to include

practice guidelines (CPGs) for SIHD have been released,

every conceivable patient presentation and maintain a

and new clinical trials extending the knowledge and evi-

workable document for clinicians. The writing group ac-

dence around coronary revascularization have been pub-

knowledges that the current AUC do not evaluate all pa-

lished (3,4). These trials include studies not only on the

tient variables that might affect 1 or more strategies for

use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), but also

the management of patients with CAD. Examples of con-

on coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), medical

ditions not explicitly considered within the scenarios

therapy, and diagnostic technologies such as fractional

include severe chronic kidney disease, severe peripheral

flow reserve

(FFR) to guide revascularization

(5-8).

vascular disease, known malignancies, poor lung func-

Additional studies, some based on data from the National

tion, advanced liver disease, advanced dementia, and/or

Cardiovascular Data Registry

(NCDR), have been pub-

other comorbidities that might have excluded patients

lished providing insights into practice patterns and in-

from the clinical trials that provide the evidence base for

formation around clinical scenarios and patient features

coronary revascularization. Nevertheless, it is necessary

not previously addressed (9-13).

for the clinician to include these conditions in the final

Improvements in our understanding of the variables

decision-making process for an individual patient, and

affecting patient outcomes before and after coronary

this may result in the actual therapy deviating from the

revascularization, continued emphasis on the role of

AUC rating. It is expected that all clinicians will occa-

medical therapy for coronary artery disease (CAD), and an

sionally treat patients with extenuating conditions that

increasing emphasis on shared decision making and pa-

are not captured in the current AUC, and this could result

tient preferences also make a revision of the coronary

in a treatment rating of “rarely appropriate” for the cho-

revascularization AUC timely (14). This document focuses

sen therapy in a specific patient. However, these situa-

on SIHD and is a companion to the AUC specifically for

tions should not constitute a majority of treatment

acute coronary syndromes.

decisions, and it is presumed that they will affect all

practitioners equally, thereby minimizing substantial

2. METHODS

biases in assessing the performance of individual clini-

cians compared with their peers. Additionally, these AUC

Indication Development

were developed in parallel with efforts to update data

A multidisciplinary writing group consisting of cardio-

collection within the NCDR registries to include data

vascular health outcomes researchers, interventional

fields that capture some of these extenuating circum-

cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, and general car-

stances, thereby improving the characterization of sce-

diologists was convened to review and revise the prior

narios in the AUC.

coronary revascularization AUC. The writing group was

AUC documents often contain specific clinical sce-

tasked with developing clinical indications

(scenarios)

narios rather than the more generalized situations

that reflect typical situations encountered in everyday

covered in CPGs; thus, subtle differences between these

practice that were then rated by a technical panel. In this

documents may exist. The treatment of patients with

document, the term “indication” is used interchangeably

SIHD should always include therapies to modify risk

with the phrase “clinical scenario.” Critical data elements

factors and/or reduce cardiovascular events—so-called

and mapping of the criteria to the elements will be pro-

secondary prevention. In several CPGs, the phrase

vided for end-users of the revascularization AUC so that

“guideline-directed medical therapy” is used and,

procedure notes and chart abstraction can be more easily

depending on the context, may include the use of anti-

mapped to the AUC. A key goal of this effort is to leverage

anginal therapy in addition to therapies for secondary

the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) Cath-

prevention. In this AUC, it is assumed that all patients will

PCI registry to map indications to appropriateness ratings,

be receiving comprehensive secondary prevention thera-

so that minimal additional data collection is needed to

pies as needed. Antianginal therapy has a central role in

support quarterly feedback to sites of their performance

the treatment of patients with SIHD. In some patients, it

as a foundation for improving patient selection for

may be the sole therapy, whereas in others it may be

revascularization. The AUC Task Force is committed to

continued, albeit in lower doses, following a revasculari-

supporting linkage of the AUC with daily workflow to

zation procedure. The earlier coronary revascularization

capture the data elements needed for AUC ratings.

AUC included information about the intensity of anti-

The revascularization AUC are based on our current

anginal therapy in several scenarios, with language such

understanding of procedure outcomes plus the potential

as “receiving no or minimal anti-ischemic therapy” or

patient benefits and risks of the revascularization strate-

“receiving a course of maximal anti-ischemic therapy.”

gies examined. Although the AUC are developed to

The new AUC adopts a different format, including options

address many of the common clinical scenarios

for the initiation or escalation of antianginal therapy

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

5

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

patterned after recommendations made in the 2012 ACCF/

framework to evaluate overall clinical practice patterns

AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the Diag-

and improve the quality of care.

nosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic

In developing these AUC for coronary revasculariza-

Heart Disease (2012 SIHD guideline) (3), using a structure

tion, the rating panel was asked to rate each indication

that mimics clinical practice. However, the primary pur-

using the following definition of appropriate use:

pose of these AUCs is to rate the appropriateness of

A coronary revascularization is appropriate care

revascularization with the understanding that decisions

when the potential benefits, in terms of survival or

about revascularization are frequently made in the

health outcomes (symptoms, functional status, and/

context of ongoing antianginal therapy. Because recom-

or quality of life), exceed the potential negative

mendations for revascularization or the medical man-

consequences of the treatment strategy.

agement of CAD are found throughout several CPGs, the

AUC ratings herein are meant to unify related CPGs and

The rating panel scored each indication on a scale from

other data sources and provide a useful tool for clinicians.

1 to 9 as follows:

These AUC were developed with the intent of assisting

Score 7 to 9: Appropriate care

patients and clinicians, but they are not intended to

Score 4 to 6: May be appropriate care

diminish the acknowledged complexity or uncertainty of

clinical decision making and should not be used as a

Score 1 to 3: Rarely appropriate care

substitute for sound clinical judgment. There are

Appropriate Use Definition and Ratings

acknowledged evidence gaps in many areas where clinical

judgment and experience must be blended with patient

In rating these criteria, the rating panel was asked to assess

preferences and the existing knowledge base defined in

whether the use of revascularization for each indication is

CPGs. It is important to emphasize that a rating of

“appropriate care,”

“may be appropriate care,” or is

appropriate care does not mandate that a revasculariza-

“rarely appropriate care” using the following definitions

tion procedure be performed; likewise, a rating of rarely

and their associated numeric ranges. Anonymized indi-

appropriate care should not prevent a revascularization

procedure from being performed. It is anticipated, as

Median Score 7 to 9: Appropriate Care

noted in the previous text, that there will be occasional

clinical scenarios rated rarely appropriate in which per-

An appropriate option for management of patients in this

forming revascularization may still be in the best interest

population, as the benefits generally outweigh the risks;

of a particular patient. In situations in which the AUC

an effective option for individual care plans, although not

rating is not followed, clinicians should document the

always necessary depending on physician judgment and

specific patient features not captured in the clinical sce-

patient-specific preferences (i.e., procedure is generally

nario or the rationale for the chosen therapy. Depending

acceptable and is generally reasonable for the indication).

on the urgency of care, convening a heart team or

obtaining a second opinion may be helpful in some of

Median Score 4 to 6: May Be Appropriate Care

these settings.

At times an appropriate option for management of pa-

The AUC can be used in several ways. As a clinical tool,

tients in this population due to variable evidence or

the AUC assist clinicians in evaluating possible therapies

agreement regarding the benefit to risk ratio, potential

under consideration and can help better inform patients

benefit based on practice experience in the absence of

about their therapeutic options. As an administrative and

evidence, and/or variability in the population; effective-

research tool, the AUC provide a means of comparing

ness for individual care must be determined by a patient’s

utilization patterns among providers to thereby derive an

physician in consultation with the patient on the basis of

assessment of an individual clinician’s management

additional clinical variables and judgment along with

strategies compared with his/her peers. It is critical to

patient preferences (i.e., procedure may be acceptable

understand that the AUC should be used to assess an

and may be reasonable for the indication).

overall pattern of clinical care rather than being the final

Median Score 1 to 3: Rarely Appropriate Care

arbitrator of specific individual cases. The ACC and its

collaborators believe that an ongoing review of one’s

Rarely an appropriate option for management of patients

practice using these criteria will help guide more effec-

in this population due to the lack of a clear benefit/risk

tive, efficient, and equitable allocation of healthcare re-

advantage; rarely an effective option for individual care

sources, and ultimately, better patient outcomes.

plans; exceptions should have documentation of the

However, under no circumstances should the AUC be

clinical reasons for proceeding with this care option (i.e.,

used to adjudicate or determine payment for individual

procedure is not generally acceptable and is not generally

patients. Rather, the intent of the AUC is to provide a

reasonable for the indication).

6

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

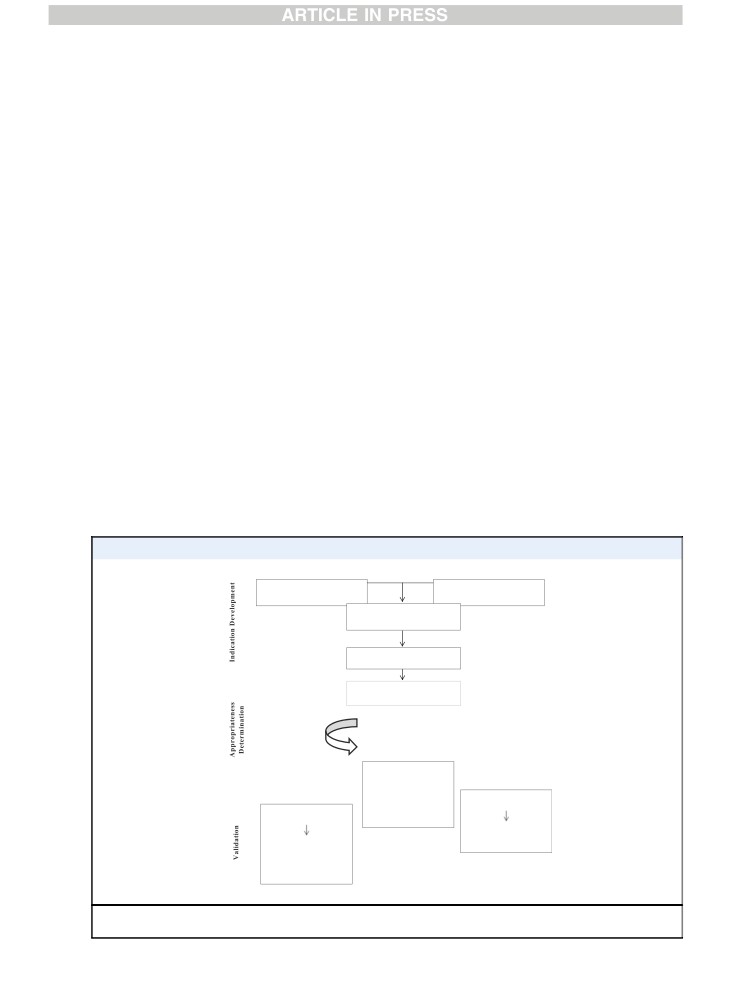

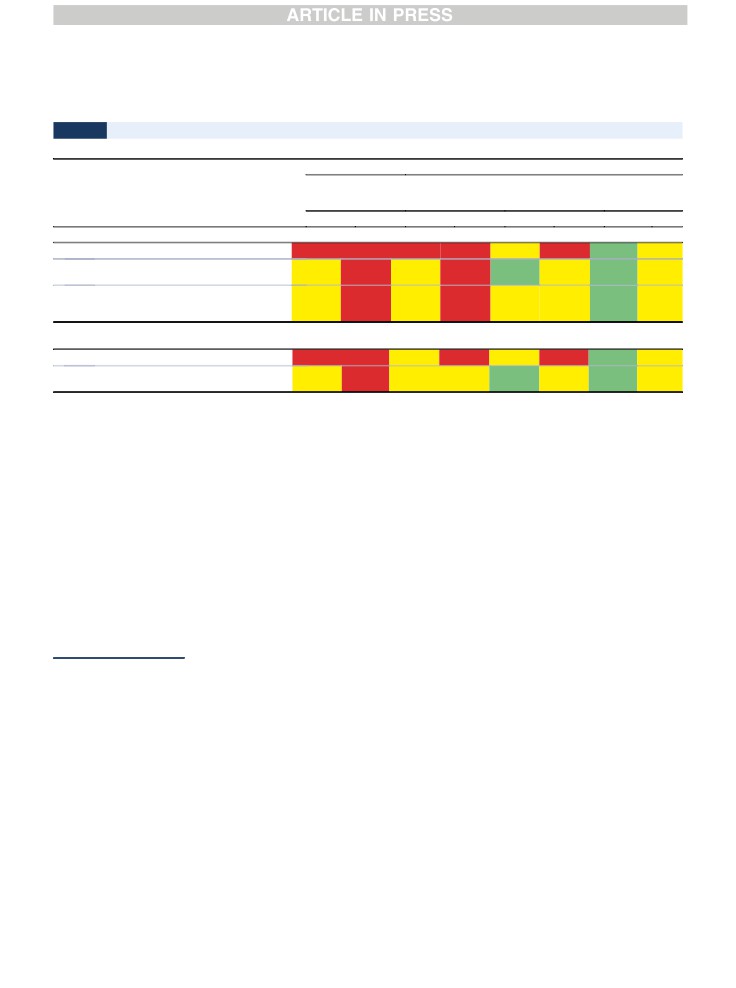

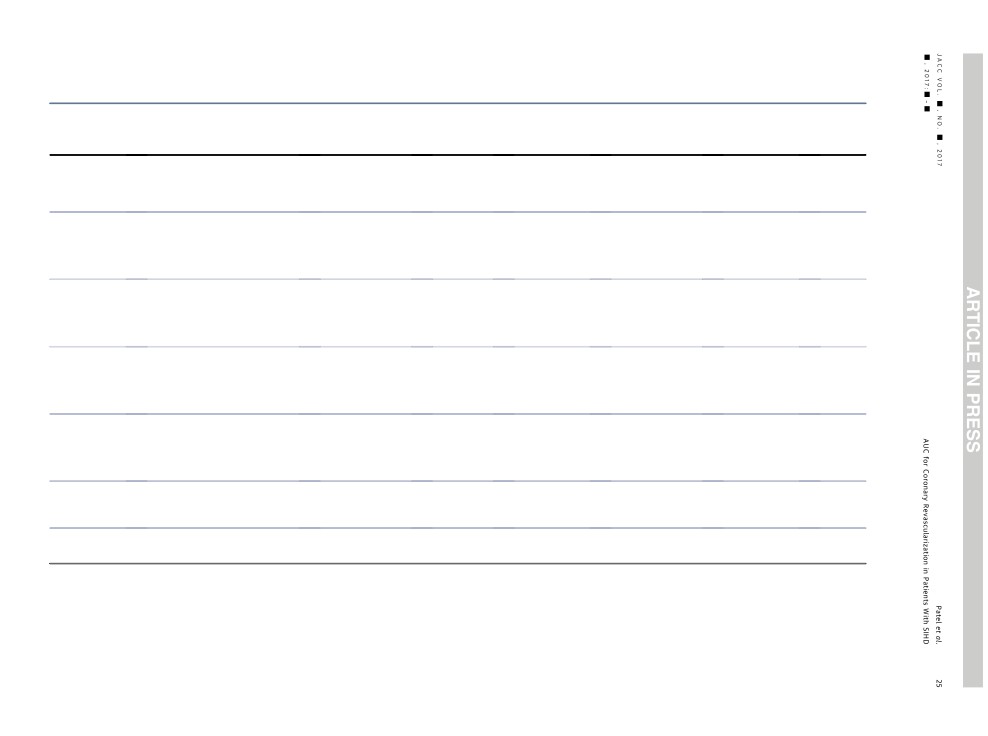

The process for development of the AUC is shown in

7. Invasive testing such as intravascular ultrasound

Figure 1 and described in detail in previous documents

(IVUS) and invasive physiology such as FFR.

(1,2).

The anatomic construct for CAD is based on the pres-

After completion and tabulation of the second round of

ence or absence of flow-limiting obstructions in the cor-

ratings, it became apparent to the writing group that the

onary arteries categorized by the number of vessels

original structure of certain rating tables may have

involved (1-,

2-, and

3-vessel, and/or left main CAD).

confused some members of the rating panel, causing

Additionally, we included in the anatomic construct the

ratings that were not internally consistent. This resulted

presence or absence of proximal left anterior descending

in a re-evaluation and redesign of the rating table struc-

(LAD) disease. This specific stenosis location was identi-

ture, which then required a third round of ratings. This

fied in both the 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary

AUC document presents the end result of that process and

artery bypass graft surgery (2011 CABG guidelines) and

the results of the third round of ratings.

2012 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary

intervention (2012 PCI guidelines) and was included in

Scope of Indications

clinical trial recruitment to guide revascularization de-

The indications for coronary revascularization in SIHD were

cisions (6,15,16). Other factors such as diabetes and the

developed considering the following common variables:

complexity of disease were included in certain clinical

1. The clinical presentation

(e.g., low or high activity

scenarios given their effect on cardiac risk and association

level to provoke ischemic symptoms);

with more favorable outcomes from surgical revasculari-

2. Use of antianginal medications;

zation. As before, noninvasive test findings are included

3. Results of noninvasive tests to evaluate the presence

in many scenarios to distinguish patients with a low risk

and severity of myocardial ischemia;

for future adverse events from those with intermediate-

4. Presence of other confounding factors and comorbid-

or high-risk findings, as these terms are routinely used in

ities such as diabetes;

clinical practice.

5. Extent of anatomic disease;

Antianginal treatment of CAD is incorporated into the

6. Prior coronary artery bypass surgery; and

structure of the tables following the pattern of

FIGURE 1

AUC Development Process

Develop list of indications,

Literature review and

assumptions, and definitions

guideline mapping

Review Panel >30 members

provide feedback

Writing Group revises

indications

Rating Panel rates the

indications in 2 rounds

1st round-no interaction

2nd round-panel interaction

Appropriate Use Score

(7-9) Appropriate

(4-6) May Be

Appropriate

Prospective clinical

(1-3) Rarely

decision aids

Prospective comparison

Appropriate

with clinical records

Increase appropriate

use

% use that is

Appropriate, May Be

Appropriate, or Rarely

Appropriate

AUC indicates appropriate use criteria.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

7

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

recommendations in the SIHD guideline (see 2012 SIHD

5. A significant coronary stenosis for the purpose of the

guidelines, Section 4.4.3.1.) but without specific drug or

clinical scenarios is defined as:

dose recommendations (3,4). In general, beta blockers are

n

≥70% luminal diameter narrowing, by visual

recommended as the initial treatment for symptom relief

assessment, of an epicardial stenosis measured in

(Class I recommendation), with calcium channel blockers,

the “worst view” angiographic projection;

long-acting nitrates, or ranolazine prescribed in combi-

n

≥50% luminal diameter narrowing, by visual

nation with beta blockers when initial treatment with beta

assessment, of a left main stenosis measured in

blockers is inadequate to control symptoms despite

the “worst view” angiographic projection; or

appropriate dosing. Calcium channel blockers, long-

n

40% to 70% luminal narrowing, by visual assess-

acting nitrates, or ranolazine should be prescribed for

ment, of an epicardial stenosis measured in the

relief of symptoms when beta blockers are contra-

“worst view” angiographic projection with an

indicated or cause unacceptable side effects. Long-acting

abnormal FFR as defined in the following text.

nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are

6. An FFR≤0.80 is abnormal and is consistent with

reasonable alternatives to beta blockers as first-line

downstream inducible ischemia.

therapy for antianginal symptoms

(Class IIa, Level of

7. All patients included in these scenarios are receiving

Evidence: B). The use of FFR was incorporated to a greater

needed therapies to modify existing risk factors as

extent than in the previous AUC as more data on the

outlined in CPGs and other documents (17-19). Despite

usefulness of this testing modality have emerged.

the best efforts of the clinician, all patients may not

achieve target goals for cardiac risk factor modifica-

tion. However, a continuing effort and plan of care to

3. ASSUMPTIONS

address risk factors are assumed to exist.

8. For patients with SIHD, the writing group recognizes

General Assumptions

there are many choices for antianginal therapy and

Specific assumptions provided to the rating panel for their

considerable variation in the use and tolerance of

use in rating the relevant clinical scenarios are summa-

antianginal medications among patients. The use of

rized in the following text.

antianginal therapy adopted in this AUC follows the

1.

When available, each clinical scenario includes the

recommendations of the SIHD guideline. Assume that

patient’s clinical status/symptom complex, ischemic

antianginal therapy is prescribed at a dose that

burden as determined by noninvasive functional

adequately controls the patient’s symptoms or is the

testing, burden of coronary atherosclerosis as deter-

maximally tolerated dose for a particular drug.

mined by angiography, and additional invasive

9. Operators performing percutaneous or surgical

testing evaluations by invasive physiology (e.g., FFR,

revascularization have appropriate clinical training

instantaneous wave-free ratio) or intravascular

and experience and have satisfactory outcomes as

imaging.

assessed by quality assurance monitoring (15,20,21).

2. When utilized, stress testing, with or without an

10. Revascularization by either percutaneous or surgical

associated imaging procedure, was performed

methods is performed in a manner consistent with

correctly and with sufficient quality to produce a

established standards of care at centers with quality/

meaningful and accurate result within the limits of

volume standards (15,20,21).

the test performance. Evidence of myocardial viability

11.

In the clinical scenarios, no unusual extenuating cir-

is also an important finding and in some clinical sit-

cumstances exist (e.g., an inability to comply with

uations may influence the decision for revasculariza-

antiplatelet agents, do-not-resuscitate status, a pa-

tion, but it was not used to further expand the number

tient unwilling to consider revascularization, tech-

of indications.

nical reasons rendering revascularization infeasible,

3. As the main focus of this AUC is revascularization,

or comorbidities likely to markedly increase proce-

assume that coronary angiography has been per-

dural risk). If any of these circumstances exist, it is

formed. The rating panel should judge the appropri-

critical that the clinician provide adequate documen-

ateness of revascularization on the basis of the clinical

tation in the medical record to support exclusions

scenario presented, including the coronary disease

from the AUC and the alternative management de-

identified, independent of a judgment about the

cisions made in the patient.

appropriateness of the coronary angiogram in the

12. Patient history and physical examination are assumed

scenario.

to be comprehensive and thorough. Descriptions of

4. Assume no other significant coronary artery stenoses

the patient’s symptoms are assumed to accurately

are present except those specifically described in the

represent the current status of the patient

(e.g.,

clinical scenario.

asymptomatic patients are truly asymptomatic rather

8

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

than asymptomatic due to self-imposed lifestyle

“Appropriate,”

“May Be Appropriate,” or

“Rarely

limitations).

Appropriate” for any given clinical indication.

13. When PCI is being considered in patients with multi-

2. If more than 1 treatment falls into the same appropriate

vessel disease, it may be clinically prudent to perform

use category, it is assumed that patient preference

the procedures in a sequential fashion

(so-called

combined with physician judgment and available local

“staged procedures”). If this is the initial management

expertise will be used to determine the final treatment

plan, the intent for a staged procedure should be

used.

clearly outlined and the appropriateness rating should

apply to the entire revascularization procedure. Spe-

4. DEFINITIONS

cifically, planned staged procedures should not be

assessed by individual arteries but rather in terms of

Definitions of some key terms used throughout the sce-

the plan for the entire revascularization strategy. For

narios are shown in the following text. A complete set of

data collection purposes, this will require document-

definitions is found in Appendix A. These definitions were

ing how the procedure is staged (either PCI or hybrid

provided to and discussed with the rating panel before

revascularization with surgery), and it is assumed that

the rating process started.

all stenoses covered under the umbrella of the plan-

ned staged procedure are functionally significant.

Indication

14. Although the clinical scenarios should be rated on the

A set of patient-specific conditions defines an “indica-

basis of the published literature, the writing committee

tion.” The term “clinical indication” (used interchange-

acknowledges that decisions about coronary artery

ably with “clinical scenario”) provides the context for the

revascularization in patient populations that are poorly

rating of therapeutic options. However, an “appropriate”

represented in the literature are still required in daily

rating assigned by the rating panel does not necessarily

practice. Therefore, rating panel members should as-

mean the therapy is mandatory, nor does a

“rarely

sume that some of the clinical scenarios presented will

appropriate” rating mean it is prohibited.

have low levels of evidence to guide rating decisions.

Risk Factor Modification (Secondary Prevention) and

Key to the application of the AUC in settings where

Antianginal Medical Therapy

there are extenuating circumstances or low levels of

supporting evidence is enhanced documentation by

As previously stated, the indications assume that patients

the clinician to support the clinical decisions made.

are receiving all indicated treatments for the secondary

15. As with all previously published clinical policies, de-

prevention of cardiovascular events. This includes life-

viations by the rating panel from prior published

style and pharmacological interventions according to

documents were directed by new evidence that jus-

guideline-based recommendations. Antianginal medical

tifies such evolution. However, the reader is advised

therapy is incorporated into the structure of the rating

to pay careful attention to the wording of an indica-

tables and should follow the recommendations of the

tion in the present document when making compari-

SIHD guideline, with a beta blocker as initial therapy and

sons to prior publications.

the option to administer calcium channel blockers, long-

16. Indication ratings contained herein supersede the

acting nitrates, and/or ranolazine if the beta blocker is

ratings of similar indications contained in previous

ineffective or not tolerated (3,4).

AUC coronary revascularization documents.

Specific target doses of drugs are not provided as this

must be individualized, but for beta blockers, it is

assumed the dose is sufficient to blunt the exercise heart

Assumptions for Rating Multiple Treatment Options

rate without causing intolerable fatigue, bradycardia, or

1. The goal of this document is to identify revasculariza-

hypotension. It is assumed that the maximally tolerated

tion treatments that are considered reasonable for a

dose of beta blockers is being used before the addition of

given clinical indication. Therefore, each treatment

other drugs, and when other drugs are added, the dose is

option (PCI or CABG) should be rated independently for

titrated to alleviate symptoms or is also the maximally

its level of appropriateness in the specific clinical sce-

tolerated dose. Using multiple drugs at less than optimal

nario, rather than being placed into a forced or artificial

doses is an inefficient and expensive strategy. The SIHD

rank-order comparison against each other. Identifying

guideline recommends calcium channel blockers or long-

options that may or may not be reasonable for specific

acting nitrates if beta blockers are contraindicated or

indications is the goal of this document, rather than

cause unacceptable side effects. The SIHD guideline also

determining a single best treatment for each clinical

recommends adding calcium channel blockers or long-

indication or a rank-order. Therefore, more than

1

acting nitrates to beta blockers for relief of symptoms

treatment or even all treatments may be considered

when initial treatment with beta blockers is unsuccessful.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

9

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

Initiating, continuing, or intensifying antianginal therapy

of the LAD proximal to the first major septal and diagonal,

is integrated into the ratings tables along with revascu-

the terms 1-, 2-, and 3-vessel disease do not define the

larization options, as this is typical of real-world practice.

location (i.e., proximal, mid, or distal) of the stenosis in the

artery, which is frequently related to the amount of

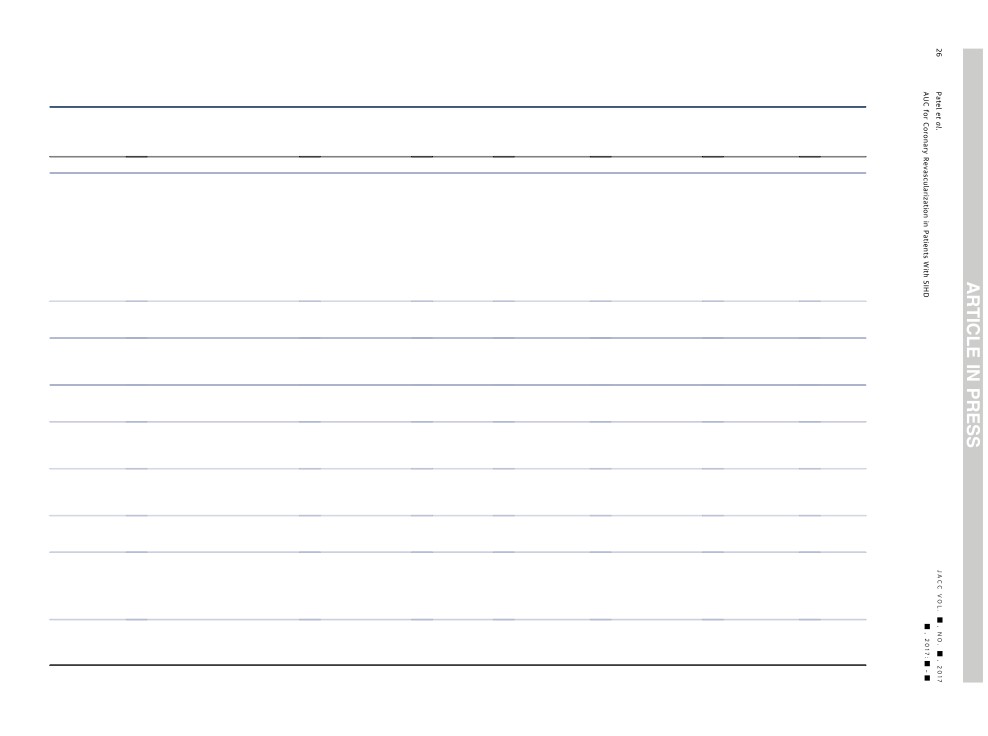

Stress Testing and Risk of Findings on Noninvasive Testing

myocardium at risk. Furthermore, the classification of

Stress testing is commonly used for both diagnosis and

diseased vessels does not consider coronary dominance,

risk stratification of patients with CAD. Therapies to

although in practical terms, most consider individuals with

improve survival in patients with SIHD are outlined in

significant disease in the LAD and a left dominant

circumflex to have

3-vessel involvement. Coronary

noninvasive findings associated with high (>3% annual

anomalies are also not considered in this construct.

death or myocardial infarction), intermediate (1% to 3%

Although imperfect, the commonly used classification of

annual death or myocardial infarction) and low

(<1%

1-, 2-, and 3-vessel disease and left main disease remains

annual death or myocardial infarction) risk are outlined in

widely used in clinical practice. Within the context of this

Table B. It is important to note that this table includes

document, the terms 1-, 2-, and 3-vessel disease should be

several noninvasive findings apart from a stress test, such

assumed to mean that each vessel involved (whether the

as resting LV function and a high coronary calcium score

main vessel or a major side branch) provides flow to a

in the assessment of risk. These were not specifically

sufficient amount of myocardium to be clinically impor-

included in the indications of this AUC, but should be

tant. The anatomic definition of 1-, 2-, or 3-vessel disease is

considered as part of the patient profile described in an

now often augmented by the physiological testing of ste-

indication, especially when high and intermediate risk are

nosis significance (e.g., FFR), which can reclassify the he-

used in the indication.

modynamic significance of a stenosis. In the setting of PCI,

when FFR in an artery is >0.80, treatment is deferred and

Vessel Disease

the clinical scenario considered should be reclassified to be

The construct used to characterize the extent of CAD is

consistent with the number of significant stenoses. In

based on the common clinical use of the terms 1-, 2-, and 3-

other words, if the angiogram suggests 2 significant ste-

vessel disease and left main disease, although it is recog-

noses, but FFR testing indicates that only 1 is significant,

nized that individual coronary anatomy is highly variable.

the clinical scenario considered should be from the group

In general, these terms refer to a significant stenosis in 1 of

with 1-vessel CAD. Although there are considerable data to

the 3 major coronary arteries (right coronary artery, LAD, or

support FFR-directed PCI treatment as an option, this

circumflex) or their major branches. With the exception of

concept is not well-established for surgical revasculariza-

the proximal LAD, which specifically refers to the segment

tion (22,23).

TABLE A Revascularization to Improve Survival Compared With Medical Therapy

Anatomic

Setting

COR

LOE

References

UPLM or complex CAD

CABG and PCI I—Heart Team approach recommended

C

(950-952)

CABG and PCI IIa—Calculation of STS and SYNTAX scores

B

(949,950,953-957)

UPLM*

CABG

I

B

(73,381,412,959-962)

PCI

IIa—For SIHD when both of the following are present:

B

(949,953,955,958,963-980)

■ Anatomic conditions associated with a low risk of PCI procedural complications and a high likelihood of

good long-term outcome (e.g., a low SYNTAX score of #22, ostial or trunk left main CAD)

■ Clinical characteristics that predict a significantly increased risk of adverse surgical outcomes

(e.g., STS-predicted risk of operative mortality ≥5%)

IIa—For UA/NSTEMI if not a CABG candidate

B

(949,968-971,976-979,981)

IIa—For STEMI when distal coronary flow is TIMI flow grade <3 and PCI can be performed more

C

(965,982,983)

rapidly and safely than CABG

IIb—For SIHD when both of the following are present:

B

(949,953,955,958,963-980,984)

■ Anatomic conditions associated with a low to intermediate risk of PCI procedural complications

and an intermediate to high likelihood of good long-term outcome (e.g., low-intermediate

SYNTAX score of <33, bifurcation left main CAD)

■ Clinical characteristics that predict an increased risk of adverse surgical outcomes

(e.g., moderate—severe COPD, disability from prior stroke, or prior cardiac surgery;

STS-predicted operative mortality >2%)

III: Harm—For SIHD in patients (versus performing CABG) with unfavorable anatomy for PCI and who are

B

(73,381,412,949,953,955,959-964)

good candidates for CABG

Continued on the next page

10

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

TABLE A Continued

Anatomic

Setting

COR

LOE

References

3-vessel disease with or without proximal LAD artery disease*

CABG

I

B

(353,412,959,985-987)

IIa—It is reasonable to choose CABG over PCI in patients with complex 3-vessel CAD

B

(964,980,987-989)

(e.g., SYNTAX score >22) who are good candidates for CABG.

PCI

IIb—Of uncertain benefit

B

(366,959,980,985,987)

2-vessel disease with proximal LAD artery disease*

CABG

I

B

(353,412,959,985-987)

PCI

IIb—Of uncertain benefit

B

(366,959,985,987)

2-vessel disease without proximal LAD artery disease*

CABG

IIa—With extensive ischemia

B

(327,990-992)

IIb—Of uncertain benefit without extensive ischemia

C

(987)

PCI

IIb—Of uncertain benefit

B

(366,959,985,987)

1-vessel proximal LAD artery disease

CABG

IIa—With LIMA for long-term benefit

B

(412 987,993,994)

PCI

IIb—Of uncertain benefit

B

(366,959,985,987)

1-vessel disease without proximal LAD artery involvement

CABG

III: Harm

B

(306,327,412,985,990,995-998)

PCI

III: Harm

B

(306,327,412,985,990,995-998)

LV dysfunction

CABG

IIa—EF 35% to 50%

B

(365,412,999-1002)

CABG

IIb—EF <35% without significant left main CAD

B

(355,365,410,412,999-1002)

PCI

Insufficient data

N/A

Survivors of sudden cardiac death with presumed ischemia-mediated VT

CABG

I

B

(350,1003,1004)

PCI

I

C

(1003)

No anatomic or physiological criteria for revascularization

CABG

III: Harm

B

(306,327,412,985,990,995-998)

PCI

III: Harm

B

(306,327,412,985,990,995-998)

*In patients with multivessel disease who also have diabetes mellitus, it is reasonable to choose CABG (with LIMA) over PCI (30,991,1005-1011) (Class IIa; LOE: B).

Reproduced from Fihn et al. (3).

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COR, class of recommendation; EF, ejection fraction; LAD, left anterior

descending; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; LOE, level of evidence; LV, left ventricular; N/A, not available; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SIHD, stable ischemic heart disease;

STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; SYNTAX, Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery; TIMI, Thrombolysis

In Myocardial Infarction; UA/NSTEMI, unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UPLM, unprotected left main disease; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

11

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

TABLE B Noninvasive Risk Stratification

High risk (>3% annual death or MI)

1. Severe resting LV dysfunction (LVEF <35%) not readily explained by noncoronary causes

2. Resting perfusion abnormalities ≥10% of the myocardium in patients without prior history or evidence of MI

3. Stress ECG findings including ≥2 mm of ST-segment depression at low workload or persisting into recovery, exercise-induced ST-segment elevation, or

exercise-induced VT/VF

4. Severe stress-induced LV dysfunction (peak exercise LVEF <45% or drop in LVEF with stress ≥10%)

5. Stress-induced perfusion abnormalities encumbering ≥10% myocardium or stress segmental scores indicating multiple vascular territories with

abnormalities

6. Stress-induced LV dilation

7. Inducible wall motion abnormality (involving >2 segments or 2 coronary beds)

8. Wall motion abnormality developing at low dose of dobutamine (#10 mg/kg/min) or at a low heart rate (<120 beats/min)

9. CAC score >400 Agatston units

10. Multivessel obstructive CAD (≥70% stenosis) or left main stenosis (≥50% stenosis) on CCTA

Intermediate risk (1% to 3% annual death or MI)

1. Mild/moderate resting LV dysfunction (LVEF 35% to 49%) not readily explained by noncoronary causes

2. Resting perfusion abnormalities in 5% to 9.9% of the myocardium in patients without a history or prior evidence of MI

3. ≥1 mm of ST-segment depression occurring with exertional symptoms

4. Stress-induced perfusion abnormalities encumbering 5% to 9.9% of the myocardium or stress segmental scores (in multiple segments) indicating 1 vascular

territory with abnormalities but without LV dilation

5. Small wall motion abnormality involving 1 to 2 segments and only 1 coronary bed

6. CAC score 100 to 399 Agatston units

7. One vessel CAD with ≥70% stenosis or moderate CAD stenosis (50% to 69% stenosis) in ≥2 arteries on CCTA

Low risk (<1% annual death or MI)

1. Low-risk treadmill score (score ≥5) or no new ST segment changes or exercise-induced chest pain symptoms; when achieving maximal levels of exercise

2. Normal or small myocardial perfusion defect at rest or with stress encumbering <5% of the myocardium*

3. Normal stress or no change of limited resting wall motion abnormalities during stress

4. CAC score <100 Agaston units

5. No coronary stenosis >50% on CCTA

*Although the published data are limited; patients with these findings will probably not be at low risk in the presence of either a high-risk treadmill score or severe resting LV

dysfunction (LVEF <35%).

Reproduced from Fihn et al. (3).

CAC indicates coronary artery calcium; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction;

and MI, myocardial infarction.

Ischemic Symptoms

variability in the assessment of symptom severity, the

Angina pectoris is usually described as a discomfort (not

writing group chose not to use the Canadian Cardiovascular

necessarily pain) in the chest or adjacent areas. It is

Society classification system in this document

(24,25).

variably described as tightness, heaviness, pressure,

Symptom status of the patient was broadly classified into

squeezing, or a smothering sensation. In some patients,

asymptomatic or simply ischemic symptoms, emphasizing

the symptom may be a more vague discomfort, a

the use of more objective measures of ischemia within each

numbness, or a burning sensation. Alternatively, so-

indication to stratify patients into low-risk or intermediate-/

called anginal equivalents such as dyspnea, faintness,

high-risk findings.

or fatigue may occur. The location is usually substernal

Invasive Methods of Determining Hemodynamic Significance

and radiation may occur to the neck, jaw, arms, back, or

epigastrium. Isolated epigastric discomfort or pain in the

The writing group recognizes that not all patients referred

lower mandible may rarely be a symptom of myocardial

for revascularization will have previous noninvasive

ischemia. The typical episode of angina pectoris begins

testing. In fact, there are several situations in which pa-

gradually and reaches its maximum intensity over a

tients may be appropriately referred for coronary angi-

period of minutes. Typical angina pectoris is precipi-

ography on the basis of symptom and ECG presentation

tated by exertion or emotional stress and is relieved

and a high pretest probability of CAD. In these settings,

within minutes by rest or nitroglycerin. Because of the

there may be situations where angiography shows a cor-

variation in symptoms that may represent myocardial

onary narrowing of questionable hemodynamic impor-

ischemia, the clinical scenarios are presented using the

tance in a patient with symptoms that can be related to

broad term

“ischemic symptoms” to capture this

myocardial ischemia. In such patients, the use of addi-

concept.

tional invasive measurements (such as FFR or intravas-

This AUC document is specific for patients with SIHD.

cular ultrasound) at the time of diagnostic angiography

Therefore, by definition, there are no Canadian Cardiovas-

may be very helpful in further defining the need for

cular Society Class 4 patients. Because of the variety of

revascularization and may substitute for stress test find-

symptoms that may indicate myocardial ischemia, individual

ings. Accordingly, many of the indications now include

patient variation in how they are described and observer

FFR test results.

12

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

The Role of Patient Preference in the AUC

BB = beta-blockers

Patients often make decisions about medical treatments

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft

without a complete understanding of their options. Pa-

CAD = coronary artery disease

tient participation or shared decision making (SDM) de-

FFR = fractional flow reserve

scribes a collaborative approach whereby patients are

IMA = internal mammary artery

provided with evidence-based information on treatment

choices and encouraged to use the information in an

LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery

informed dialogue with their provider to make decisions

LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction

that not only use the scientific evidence, but also align

PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

with their values, preferences, and lifestyle (26-28). The

SIHD = stable ischemic heart disease

alternative decision paradigm, often referred to as medi-

cal paternalism, places decision authority with physicians

and assigns the patient a more passive role (29). SDM re-

6. CORONARY REVASCULARIZATION IN

spects both the provider’s knowledge and the patient’s

PATIENTS WITH STABLE ISCHEMIC HEART

right to be fully informed of all care options with their

DISEASE: APPROPRIATE USE CRITERIA (BY

associated risks and benefits. SDM often uses decision

INDICATION)

aids such as written materials, online modules, or videos

to present information about treatment options that help

Section 1. SIHD Without Prior CABG

the patient evaluate the risks and benefits of a particular

treatment. The most effective decision aids to help pa-

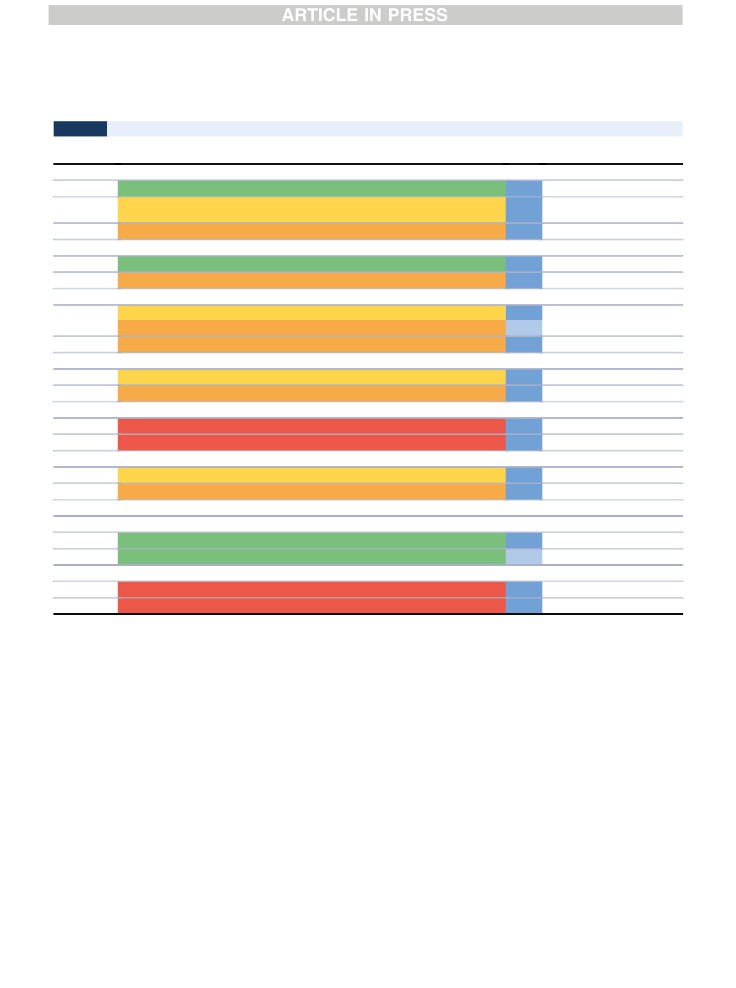

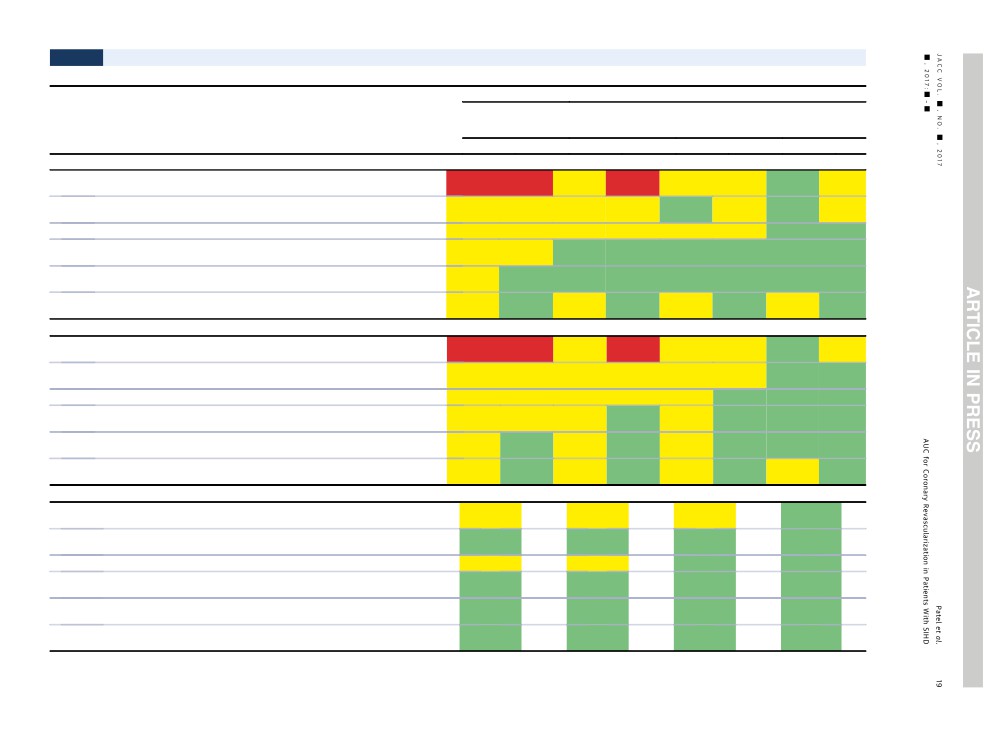

The format for tables in Section 1 is similar, with separate

tients make truly informed decisions provide relevant

tables for 1-, 2-, and 3-vessel disease and left main dis-

facts and videos of real patient perspectives regarding the

ease. The columns in each table are stratified into 2 cat-

particular treatment

(30). Many professional organiza-

egories. There is a single column combining patients who

tions now endorse SDM in practice (31,32).

are asymptomatic and not receiving antianginal therapy

More than 1 treatment option often exists with no clear

with patients who are asymptomatic and receiving anti-

evidence identifying the best option. This is compounded

anginal therapy. The remaining columns are devoted to

when there is variation in experts’ recommendations

patients with ischemic symptoms, with 3 separate cate-

about the best treatment under different circumstances

gories: ischemic symptoms and receiving no antianginal

therapy, ischemic symptoms and receiving 1 antianginal

(33). A challenging situation exists when scientific data

drug (beta blocker preferred), and ischemic symptoms

suggest 1 treatment is likely to have better outcomes, yet

receiving 2 or more antianginal drugs. As outlined in the

the patient prefers an alternative treatment. Within the

SIHD guideline, in the absence of contraindications,

context of the AUC, this would be manifest as the patient

initial therapy should be a beta blocker prescribed at a

requesting a therapy with a lower AUC rating

(e.g.,

dose that reduces heart rate without excessive resting

wanting a therapy rated as rarely appropriate when a

bradycardia, hypotension, or fatigue. Other antianginal

therapy rated appropriate exists). Informed consent is

drugs are then added to beta blockers depending on the

fundamental to SDM (34). Without understanding the pros

individual needs of the patient until symptoms are sup-

and cons of all treatment options, patients cannot properly

pressed to the satisfaction of the patient or higher doses

engage in SDM and blend their personal desires with the

cannot be used because of side effects. In each of the

scientific data. Without question, it is important that

subordinate columns, the panel was asked to rate the

blending AUC ratings into clinical decision making provide

options for revascularization, specifically PCI or CABG. As

a pathway for including patient preference and SDM.

However, the mechanism for that process is beyond the

noted earlier, the rating panel was asked to rate each

scope of this AUC document. The purpose of this docu-

revascularization option independent of the other, with

ment is to develop clinical scenarios and provide ratings of

the intent to rate each therapy on its own merits rather

those scenarios by an expert panel. A complete discussion

than in comparison to the other option. In this construct,

about treatment options with SDM can only be finalized

both revascularization options could be assigned identical

once the category of appropriate use is determined.

ratings.

In this and subsequent tables, clinical scenarios often

contain the phrase “noninvasive testing.” In this docu-

5. ABBREVIATIONS

ment, that phrase includes all forms of stress testing using

either dynamic or pharmacological stress that may be

AA = antianginal

coupled with various imaging tests. It also could include

ACS = acute coronary syndrome

other imaging, such as coronary computed tomography

AUC = appropriate use criteria

angiography or magnetic resonance imaging, to assess

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

13

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

myocardial viability. Some would favor the term “func-

the equivalent of 2-vessel disease (i.e., right coronary

tional testing,” but the writing committee did not view

artery and circumflex disease). Following this construct,

this as inclusive of computed tomography or magnetic

the combination of proximal LAD disease and proximal

resonance imaging and thus favored the term “noninva-

left dominant circumflex disease would be considered as

sive testing.” FFR is considered as part of an invasive

3-vessel disease and rated using the 3-vessel disease table

evaluation and is cited separately in some scenarios. An

(

Table

1.3.

). In the absence of exercise data, invasive

emerging technology, computed tomography-derived

physiological testing of both involved vessels is included

FFR is a combination technique that is noninvasive like

in several of the indications. To remain in this table of

computed tomography but provides FFR, which has

2-vessel disease, such testing must be abnormal in both

traditionally only been an invasive test.

vessels. If this testing shows only 1 vessel to be abnormal,

the patient would no longer be rated using this table, but

Table 1.1. One-Vessel Disease

rather would be rated in the table for

1-vessel CAD.

Similar to the 2011 CABG and 2012 SIHD guidelines, this

Finally, because of the increasing body of literature that

document uses proximal LAD disease as an additional

has identified diabetes as an important factor to consider

anatomic discriminator for 1-vessel CAD. Although data

when recommending revascularization, scenarios indi-

are minimal, the writing committee felt that proximal

cating the presence of diabetes are provided.

disease of a dominant circumflex should be considered as

high-risk anatomy with similar implications as proximal

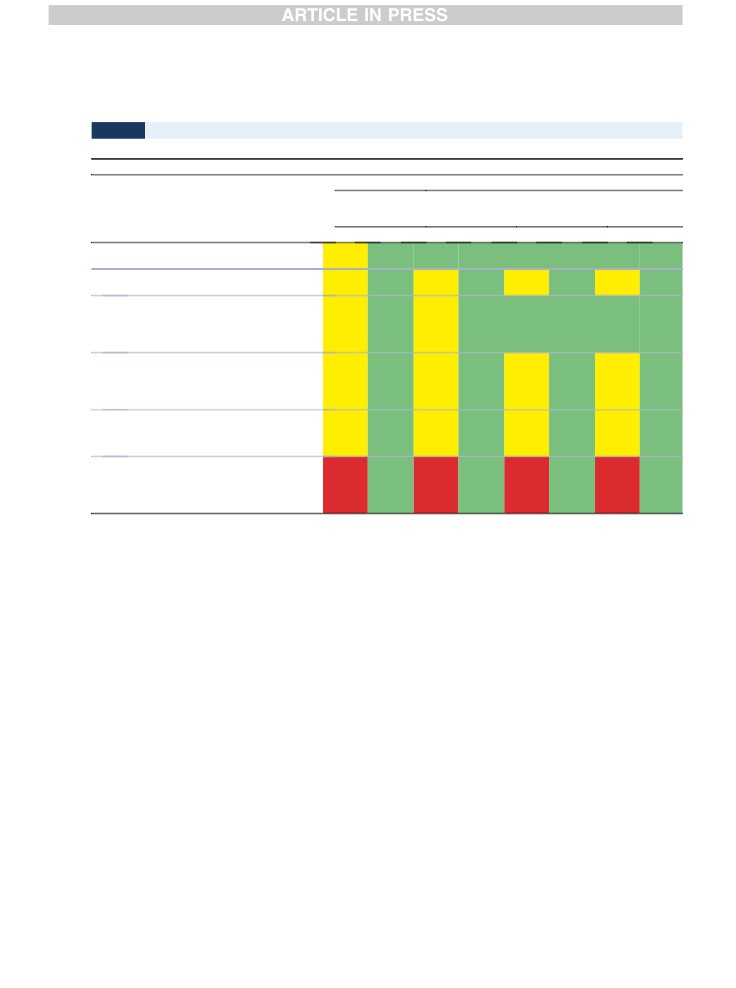

Table 1.3

. Three-Vessel Disease

LAD disease, and thus, it was considered in a separate

Similar to Table 1.2, because of the increasing body of

section along with proximal LAD disease.

literature that has identified diabetes as an important

factor to consider when recommending revascularization,

Table 1.2 Two-Vessel Disease

categories indicating the presence or absence of diabetes

The format of this table is similar to that for 1-vessel

are provided among the individual indications. Stenosis

disease. Similar to the 2011 CABG and 2012 SIHD guide-

complexity is also an important factor to consider in any

lines, this document makes a distinction regarding the

revascularization procedure, probably more so for PCI

presence or absence of proximal LAD disease. The writing

than for CABG. The SYNTAX (Synergy between Percuta-

group did not add proximal left dominant circumflex

neous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac

disease as an additional discriminator, because most

Surgery) trial provided a comprehensive comparison of

would consider an isolated stenosis in this location to be

PCI and CABG and a structure that may be helpful in

TABLE 1.1

One-Vessel Disease

Appropriate Use Score (1-9)

One-Vessel Disease

Asymptomatic

Ischemic Symptoms

Not on AA

Therapy or With

Not on AA

On 1 AA Drug

AA Therapy

Therapy

(BB Preferred)

On ≥2 AA Drugs

Indication

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

No Proximal LAD or Proximal Left Dominant LCX Involvement

1.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

R (2)

R (1)

R (3)

R (2)

M (4)

R (3)

A (7)

M (5)

2.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (4)

R (3)

M (5)

M (4)

M (6)

M (4)

A (8)

M (6)

noninvasive testing

3.

■ No stress test performed or, if performed,

M (4)

R (2)

M (5)

R (3)

M (6)

M (4)

A (8)

M (6)

results are indeterminate

■ FFR #0.80*

Proximal LAD or Proximal Left Dominant LCX Involvement Present

4.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

R (3)

M (4)

M (4)

M (5)

M (5)

A (7)

A (7)

5.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (5)

M (5)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

A (8)

noninvasive testing

6.

■ No stress test performed or, if performed,

M (5)

M (5)

M (6)

M (6)

M (6)

M (6)

A (8)

A (7)

results are indeterminate

■ FFR #0.80

The number in parentheses next to the rating reflects the median score for that indication. *iFR measurements with appropriate normal ranges may be substituted for FFR.

A indicates appropriate; AA, antianginal; BB, beta blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; FFR, fractional flow reserve; iFR, instant wave-free ratio; LAD, left anterior descending coronary

artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; M, may be appropriate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and R, rarely appropriate.

14

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

TABLE 1.2

Two-Vessel Disease

Appropriate Use Score (1-9)

Two-Vessel Disease

Asymptomatic

Ischemic Symptoms

Not on AA

Therapy or With

Not on AA

On 1 AA Drug

AA Therapy

Therapy

(BB Preferred)

On ≥2

AA Drugs

Indication

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

No Proximal LAD Involvement

7.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

R (3)

R (2)

M (4)

R (3)

M (5)

M (4)

A (7)

M (6)

8.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (5)

M (4)

M (6)

M (5)

A (7)

M (6)

A (8)

A (7)

noninvasive testing

9.

■ No stress test performed or, if performed,

M (5)

M (4)

M (6)

M (4)

A (7)

M (5)

A (8)

A (7)

results are indeterminate

■ FFR #0.80* in both vessels

Proximal LAD Involvement and No Diabetes Present

10.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

M (4)

M (5)

M (5)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

11.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

A (8)

noninvasive testing

12.

■ No stress test performed or, if performed,

M (6)

M (6)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

A (8)

results are indeterminate

■ FFR #0.80 in both vessels

Proximal LAD Involvement With Diabetes Present

13.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

M (5)

M (4)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

14.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (5)

A (7)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

A (8)

A (9)

noninvasive testing

15.

■ No stress test performed or, if performed,

M (5)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

A (7)

A (8)

results are indeterminate

■ FFR #0.80 in both vessels*

The number in parentheses next to the rating reflects the median score for that indication. *iFR measurements with appropriate normal ranges may be substituted for FFR.

A indicates appropriate; AA, antianginal; BB, beta blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; FFR, fractional flow reserve; iFR, instant wave-free ratio; LAD, left anterior descending coronary

artery; M, may be appropriate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and R, rarely appropriate.

formulating revascularization recommendations

(35).

procedures and, more recently, comparisons with PCI in

Factors such as vessel occlusion, bifurcation or trifurca-

some anatomic situations. There are data suggesting that

tion at branch points, ostial stenosis location, length

stenting of the left main ostium or trunk is more

>20 mm, tortuosity, calcification, and thrombus all add to

straightforward than treating distal bifurcation or trifur-

the complexity of PCI. The presence of multiple complex

cation stenoses and is associated with a lower rate of

features

(SYNTAX score >22) is associated with more

restenosis. In comparison, left main lesion location has a

favorable outcomes with CABG. Although limitations of

negligible influence on the success and long-term results

the SYNTAX score for certain revascularization recom-

of CABG. Accordingly, there are separate rating options

mendations are recognized and it may be impractical to

for ostial and mid-shaft left main disease and distal or

apply this scoring system to all patients with multivessel

bifurcation left main disease. The definition of a signifi-

disease, it is a reasonable surrogate for the extent and

cant left main stenosis used herein is ≥50% narrowing by

complexity of CAD and provides important information

angiography. However, the angiographic assessment of

that can be helpful when making revascularization

the severity of left main disease has several shortcomings,

decisions.

and other assessments such as IVUS or FFR may be

Accordingly, in this table specifically for patients with

needed. For left main coronary artery stenoses, a mini-

3-vessel disease, the rating panel was asked to consider

mum lumen diameter of <2.8 mm or a minimum lumen

the indications in patients with low complexity compared

area of

<6 mm2 suggests a physiologically significant

with those with intermediate and high complexity.

lesion. It has been suggested that a minimum lumen area

>7.5 mm2 suggests revascularization may be safely de-

Table 1.4. Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

ferred. A minimum lumen area between 6 and 7.5 mm2

Literature on the treatment of significant left main dis-

requires further physiological assessment, such as mea-

ease is dominated by surgical revascularization

surement of FFR. Alternatively, FFR may be used as the

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

Patel et al.

15

■, 2017:■-■

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

TABLE 1.3

Three-Vessel Disease

Appropriate Use Score (1-9)

Three-Vessel Disease

Asymptomatic

Ischemic Symptoms

Not on AA

Therapy or With

Not on AA

On 1 AA Drug

AA Therapy

Therapy

(BB Preferred)

On ≥2

AA Drugs

Indication

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

Low Disease Complexity (e.g., Focal Stenoses, SYNTAX #22)

16.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

M (5)

M (5)

M (5)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

■ No diabetes

17.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

A (8)

A (8)

noninvasive testing

■ No diabetes

18.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

M (6)

M (5)

M (6)

M (6)

A (7)

A (7)

A (8)

■ Diabetes present

19.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (6)

A (7)

M (6)

A (8)

A (7)

A (8)

A (7)

A (9)

noninvasive testing

■ Diabetes present

Intermediate or High Disease Complexity (e.g. Multiple Features of Complexity as Noted Previously, SYNTAX >22)

20.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

M (6)

M (4)

A (7)

M (5)

A (7)

M (6)

A (8)

■ No diabetes

21.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (5)

A (7)

M (6)

A (7)

M (6)

A (8)

M (6)

A (9)

noninvasive testing

■ No diabetes

22.

■ Low-risk findings on noninvasive testing

M (4)

A (7)

M (4)

A (7)

M (5)

A (8)

M (6)

A (9)

■ Diabetes present

23.

■ Intermediate- or high-risk findings on

M (4)

A (8)

M (5)

A (8)

M (5)

A (8)

M (6)

A (9)

noninvasive testing

■ Diabetes present

The number in parentheses next to the rating reflects the median score for that indication.

A indicates appropriate; AA, antianginal; BB, beta blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; M, may be appropriate; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and SYNTAX, Synergy between

PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery trial.

first modality to assess ambiguous left main severity, and

be particularly challenging because of the usual marked

the criteria for a significant stenosis are the same as for

size difference between the SVG and native artery.

non-left main stenosis (21,36,37).

Although FFR measurements are well-validated in

native vessels, data on the use of FFR in vein grafts are

limited

(38). After CABG surgery, the bypass conduit

Patients with prior CABG surgery can present with a wide

should act in a similar fashion to the native, low-

spectrum of disease progression. This includes the

resistance epicardial vessel. However, the assessment

development of new obstructive disease in coronary ar-

of ischemia due to a stenosis in a vein graft is compli-

teries not bypassed in the first operation, new stenoses in

cated by several features, which include: 1) the poten-

existing bypass grafts, and territory previously bypassed

tial for competing flow

(and pressure) from both the

but jeopardized again because of graft occlusion. Devel-

native and conduit vessels; 2) the presence of collaterals

oping indications inclusive of all of these anatomic pos-

from longstanding native coronary occlusion; and 3) the

sibilities would be impractical. Accordingly, the writing

potential for microvascular abnormalities due to

committee adopted a more compact construct based on

ischemic fibrosis and scarring, pre-existing or bypass

the presence of a significant stenosis in a bypass graft or

surgery-related myocardial infarction, or chronic low-

native coronary artery supplying

1,

2, or

3

distinct

flow ischemia. Despite these complicating features, the

vascular territories roughly corresponding to the terri-

theory of FFR should apply equally to both a lesion in

tories of the

3 main coronary arteries. As in patients

an SVG to the right coronary artery feeding a normal

without prior CABG, the indications included an assess-

myocardial bed and a lesion in the native right coro-

ment of risk based on noninvasive testing (low versus

nary. However, if the native and collateral supply

intermediate or high risk).

are sufficiently large, the FFR across an SVG stenosis

Evaluation of the severity and physiological signifi-

could be normal. FFR measurements may be most

cance of a stenosis in saphenous vein grafts (SVG) can

useful in the setting of an occluded bypass graft to a

16

Patel et al.

JACC VOL.

■, NO. ■, 2017

AUC for Coronary Revascularization in Patients With SIHD

■, 2017:■-■

TABLE 1.4

Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

Appropriate Use Score (1-9)

Left Main Disease

Asymptomatic

Ischemic Symptoms

Not on AA

Therapy or With

Not on AA

On 1 AA Drug

AA Therapy

Therapy

(BB Preferred)

On ≥2 AA Drugs

Indication

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

PCI

CABG

24.

■ Isolated LMCA disease

M (6)

A (8)

A (7)

A (8)

A (7)

A (9)

A (7)

A (9)

■ Ostial or midshaft stenosis

25.

■ Isolated LMCA disease

M (5)

A (8)

M (5)

A (8)

M (5)

A (9)

M (6)

A (9)

■ Bifurcation involvement

26.

■ LMCA disease

M (6)

A (8)

M (6)